Report on the ways local governance is changing in the areas under Ansar Allah’s control. Focuses on Ansar Allah’s takeover of local institutions, renewed efforts to collect taxes and other revenue, increased centralisation, and a collapse of local budgets and salaries. War, the economic blockade of Yemen, Ansar Allah’s policies, and international aid have combined to hollow out the existing local authority structures in Yemen.

The Berghof Foundation has been working with local authorities and the central administration(s) in Yemen since 2017 to strengthen inclusive local governance, support the resolution of local conflicts, and ensure that key concerns from the local level feed into central policy-making and the peace process.

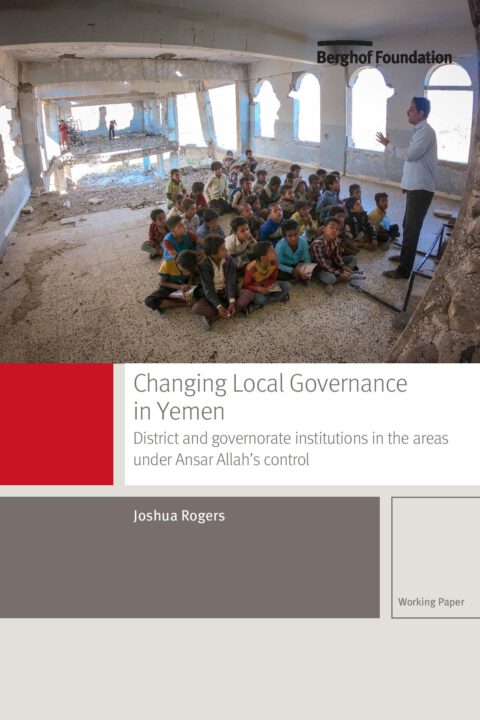

This working paper contributes to these overall goals by exploring how local governance is changing in the areas under Ansar Allah’s control. Subsequent papers will explore local-level changes in other parts of Yemen, notably in Aden and Hadhramawt. The peace process will need to take these ongoing changes into account.

Only a clear-eyed assessment of the evolving context can serve as a starting point for a realistic agreement and allow a transitional dialogue to work towards local governance arrangements that address important long-term drivers of conflict, particularly adequate service provision and social and political inclusion.

In the areas of Yemen under Ansar Allah’s control, the war and recent policy changes have together led to significant changes to local governance. There has been, first, a multi-phase takeover of local institutions. Ansar Allah appointees and networks of ‘supervisors’ have displaced the dominance of the former ruling party, the General People’s Congress (GPC), and its networks of patronage at the local level. Second, the state is now more visible and present at the local level, due to renewed efforts to collect taxes and other revenue and due to increased centralisation, coupled with new forms of central oversight and control. Together, this has created a significantly more centralised and securitised system than that which operated under President Saleh; and this new system is extracting a greater share of resources from the domestic economy. Finally, there has been a collapse of local budgets and salary payments. These financial shortfalls, caused by war and a blockade of Ansar Allah-controlled territory, have coincided with limited investment in service delivery as scarce resources were redirected to security and military institutions. As a result, responsibility for services has fallen to international aid organisations. Ultimately, war, the economic blockade of Yemen, Ansar Allah’s policies and international aid have combined to hollow out the existing local authority structures in Yemen.

These changes matter because they are likely to have long-term implications. The system remains in flux, but as patterns become more established, they will become facts on the ground that constrain options for the post-war period. The ongoing centralising legal and administrative changes to formal state structures and the creation of parallel supervisory networks will likely prove difficult to roll back. The legal and constitutional provisions of an eventual settlement will have to contend with this high level of de facto control from Sana‘a, exercised in multiple overlapping ways.

The future of increased taxation and of local governance with limited service delivery obligations is less certain. If, in the context of a peace agreement, central government regains access to oil and gas revenue, the perceived need to extract as much as possible from the local level may ease and central authorities may relax the current intensive efforts to collect funds locally. Citizens and business owners would likely breathe a sigh of relief. On the other hand, wartime increases in taxation have proven remarkably durable in other contexts and the link between higher taxation and better services appears robust across a broad range of contexts. In the medium term, there is hope that a Yemeni state that taxes more may also be pushed to provide better services to its population, and that an end to the war would free up resources for investment in local services.

Other resources you may be interested in:

Environmental Pathways for Reconciliation in Yemen

In consultations with more than 2,400 Yemenis across nine governorates, the report explores public perceptions of environmental issues and their influence on peacemaking, as well as public support for potential environmental peacemaking solutions.

Water-related Conflict Assessment Report

Report analysing water related conflicts in Abyan, Dhamar, and Hadhramout governorates, to build evidence, knowledge and understanding of water-conflicts, and to provide conflict-sensitive programming recommendations.

Analyzing Yemen’s health system at the governorate level amid the ongoing conflict: a case of Al Hodeida governorate

Study analysing public health governance at governorate level in Al Hodeida.